The show is a journey in a time machine driven by a remarkably elegant and fit pilot. It begins in 1976, in a low-end hotel behind the Saint-Lazare train station in Paris, after a gig with the then-unknown band. "We were playing in front of very few people, and they were sleeping in crappy hotels. That night I was in this 'hole' frequented by 'fireflies' and their clients," Sting recounts. "I was smitten by one of them, and I went back to my room to write a song. A song with a name in its title, for me the spirit of romance, the quintessence of courtly love": Roxanne.

A musical journey that continues through bars and disastrous auditions: "Hey man, I want to listen to hit songs, not yours," the singer continues, imitating the tone of his detractor at the time. "At that point, with nothing left to lose, I picked up my guitar and said, 'You're making a huge mistake, because one day this song is going to be a huge hit.'" Never was a prophecy more accurate, with Message in a Bottle still making fans explode with excitement today.

From here, with a rewind/forward effect, a succession of more and less recent songs begins, drawn from his time with the Police and his solo career, spanning punk, reggae, black music, jazz, classical music, musical theatre, the Caribbean, and the Far East. This culminates in The Bridge, the album of unreleased material recorded during lockdown, out November 13th: a new series of pop-rock songs that, according to the former Police member, were "written in a year of global pandemic, personal loss, separation, disruption, lockdown, and extraordinary social and political turmoil," he explains. "It was definitely the right time for me to make a record, but the circumstances were unique. It's hard to get people together in one place, so I did a lot of recording remotely via Zoom and studio technology. The theme of the record is really about building bridges between separations. I didn't start out that way—I was just writing songs—but at a certain point in the process I said, 'Oh, this is what it's about.'" The Bridge tackles heavy topics, but the single, "If It's Love," released on September 1st, is a brilliant pop song. "It's the most outlandish on the album, so I thought, 'Why not?' Any song with a whistle in it is a winner for me. It's true, I'm often drawn to problematic or complex music. I like puzzles and I like solving them. But every now and then, you have to put that aside and do something simple. A major chord followed by a rounded minor: it's the oldest trick in the book."

To promote The Bridge (April 2, 2022, at the Pala Alpitour in Turin and July 19 in Parma), the "sting" will interrupt his Las Vegas engagement, only to resume it in June next year. But what did the young punk from the early Police think of Las Vegas? "It would have evoked Frank Sinatra, the Rat Pack. Then Elvis, Tom Jones, Engelbert Humperdinck. All great artists, but they seemed trapped in this world. Vegas was a closed system and I never liked it much; the idea of a 'residency' seemed like a kind of prison sentence. Now it's not like that at all: four shows in seven days for three weeks doesn't seem like such a burden to me."

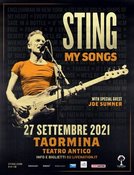

The important thing for Sting is to be back on stage after a two-year hiatus spent in studios around the world and at his estate between Figline and Incisa Valdarno, "Il Palagio," in the Chianti hills. This estate, constantly evoked by the United Kingdom, was when, at the height of the pandemic, he posted wistful videos saying, "I miss you Italy, you're my favorite country." And it matters little that last night, instead of the vast crowds in Taormina, he found himself in front of just under 1,600 spectators, due to the reduced capacity of the Ancient Theater due to the health emergency. "It's a return to my life." Unlike some of his colleagues, he has been vaccinated. "Of course," he comments. "I'm old enough to remember polio, the children on my street who were paralyzed by a disease that was eradicated very quickly by vaccines." And to his friends like Eric Clapton and Van Morrison, who have a different view, he replies: "We're all entitled to our opinions. But I think it's dangerous to tell people, 'Don't trust vaccines.' I mean, 'What are you saying that about?' It's certainly not supported by science."

(c) Sicilian Post by Giuseppe Attardi